. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

›Materialprobe‹ is the name of a series of colloquia we and the members of our network are holding at different locations. These working meetings are centered around presentations of case studies conducted as part of the research initiative, each of which investigates an example of a field or a mode of scientific writing and drawing by focusing directly on the material. The ›Materialprobe‹ events present an opportunity to introduce different ways of approaching the material and to discuss the development of methodology and the theoretical objectivity of »paper tools«.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Under the title ›Nachlese‹ (i.e. pickings), at irregular intervals we host a reading group that discusses new publications and classical texts on the subject of the research initiative, among each other and with their authors.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Wissenschaftskolleg Berlin, March 19, 2008

In cooperation with Rüdiger Campe (Yale University) we discussed the concept of ›Verfahren‹ (i.e. process, device, operation) as it is used in philosophy, literary studies, technology and jurisprudence. The intention was to sharpen conceptually the term as a tool in the analysis of cultural production.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, December 12, 2008

The event was conceived by Christof Windgätter and is taking place in cooperation with the research initiative »Knowledge in the Making.« It expands the initiative's perspective on writing and drawing by looking at the way printed matter is published. On the basis of concrete materials and examples, the workshop poses the question as to the importance of the design aspects of books, newspapers and journals for the production of scientific knowledge. Thus what is printed is no longer only, and above all not primarily, observed under commercial-distributive, political-social, aesthetic-bibliophile or technical-instrumental aspects, instead the epistemic function of the given external cover of the text shifts to the foreground: from typographical features, question of format and color, to the design of cover pages and title pages, all the way to the design of print series, trademarks and presentation media.

The event was conceived by Christof Windgätter and is taking place in cooperation with the research initiative »Knowledge in the Making.« It expands the initiative's perspective on writing and drawing by looking at the way printed matter is published. On the basis of concrete materials and examples, the workshop poses the question as to the importance of the design aspects of books, newspapers and journals for the production of scientific knowledge. Thus what is printed is no longer only, and above all not primarily, observed under commercial-distributive, political-social, aesthetic-bibliophile or technical-instrumental aspects, instead the epistemic function of the given external cover of the text shifts to the foreground: from typographical features, question of format and color, to the design of cover pages and title pages, all the way to the design of print series, trademarks and presentation media.

The historical emphasis of the workshops is on the period between 1850 and 1950, since it was during this time that reforms in publishing and trade intersected with technical innovations and changes in graphic printing, with lasting effects. The goal is to initiate discussion, among not only researching scientists but also specialists in book design, at the center of which are concrete objects.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

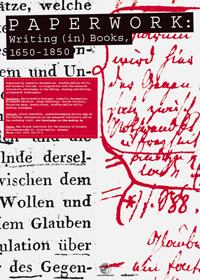

Workshop »Paperwork: Writing (in) Books, 1650 – 1850«

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin, June 17, 2010

It is a well-known paradox that the printing revolution produced more manuscripts then ever before: notes in the margins of printed works, commonplace books, and other forms of compiling notes and excerpts, letters communicating thoughts on readily available works, all of these and more contributed to an explosion not only of handwritten material derived from new publications, but, in turn, also of printed material issued from these collections of manuscript notes. The fluctuating frontiers between manuscript and print bring to mind the physics of connected vessels, and in the case of early modern Europe, of ever larger vessels. What has been described as information overload by Ann Blair and Brian Ogilvie was in fact the consequence of this growing interaction between print and manuscript. The techniques of »paperwork« (Latour) that were developed to deal with growing amounts of information were after all the same techniques that nurtured further growth.

It is a well-known paradox that the printing revolution produced more manuscripts then ever before: notes in the margins of printed works, commonplace books, and other forms of compiling notes and excerpts, letters communicating thoughts on readily available works, all of these and more contributed to an explosion not only of handwritten material derived from new publications, but, in turn, also of printed material issued from these collections of manuscript notes. The fluctuating frontiers between manuscript and print bring to mind the physics of connected vessels, and in the case of early modern Europe, of ever larger vessels. What has been described as information overload by Ann Blair and Brian Ogilvie was in fact the consequence of this growing interaction between print and manuscript. The techniques of »paperwork« (Latour) that were developed to deal with growing amounts of information were after all the same techniques that nurtured further growth.

The workshop will concentrate on the interaction between print and manuscript, focusing especially on note-taking within printed books: marginalia, annotations, drawings... The participants will investigate what pushed authors and scholars to inscribe the books they acquired, what can be inferred from these inscriptions, and how far the historian or philosopher can interpret these seemingly very spontaneous reactions to a text in relations to an author's work or thoughts. Coming from different disciplines such as natural history or the history of the book, it is hoped that the participants will, through an interdisciplinary discussion, bring new light to the way annotating, writing, and ultimately thinking was undertaken from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. The workshop is organized by Isabelle Charmantier (Exeter), Cornelia Ortlieb (Berlin) and Staffan Müller-Wille (Exeter) in cooperation with the Research Initiative »Knowledge in the Making.«

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Workshop »Tacit Knowing: Manual Knowledge in Art, Science and Technology«

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

IKKM – International Research Institute for Cultural Technologies and Media Philosophy, Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, December 15–16, 2010

The workshop will focus on an especially crucial concept at the threshold between art and science, namely that of »tacit knowing.« First described by the Hungarian physical chemist and philosopher of science Michael Polanyi in a series of lectures given in 1951–52, this form of soft knowledge – in opposition to explicit ways of knowing – is closely bound to (manual or more generally bodily) experience and is difficult or nearly impossible to verbalize or formalize.

The workshop will focus on an especially crucial concept at the threshold between art and science, namely that of »tacit knowing.« First described by the Hungarian physical chemist and philosopher of science Michael Polanyi in a series of lectures given in 1951–52, this form of soft knowledge – in opposition to explicit ways of knowing – is closely bound to (manual or more generally bodily) experience and is difficult or nearly impossible to verbalize or formalize.

In the last twenty years the concept of tacit knowing has been imported into the field of economics and work study. Not less significantly, architects and designers began to describe their work as a kind of practice-based research, which stood in contradiction to the widely held opinion that processes of developing new forms could be explained in the manner of rational, fully comprehensible protocols. The workshop wants to reconsider Polanyi’s concept and its application in the study of drafting processes in architecture, science and technology. If the generation of new forms, spaces and scientific objects is indeed closely bound to implicit, practical competences and skills, then: in what way and in which (epistemological) situations does it come into play? How is it acquired and transmitted? What is the relation between media, tools and implicit ways of knowing? Against a normative understanding of knowledge, the workshop aims to outline an amorphous field of practical competences and generative skills that always come into play when the trained body of an architect, engineer or scientist interacts manually with objects, instruments and media.