Since the middle of the 1990's, drawing has made a comeback. After its experimental, process-oriented discourse on the tide of Minimal, Concept and Performance Art, the renewed interest in drawing makes it one of the preferred media of the latest generation of artists. A vast range of recent exhibitions bears witness to this spectacular comeback. The art world of today, and its international shows, remains unthinkable without drawing. But what is it that makes the drawing of the last two decades so special and so attractive for both the producer as well as for the beholder?

Since the middle of the 1990's, drawing has made a comeback. After its experimental, process-oriented discourse on the tide of Minimal, Concept and Performance Art, the renewed interest in drawing makes it one of the preferred media of the latest generation of artists. A vast range of recent exhibitions bears witness to this spectacular comeback. The art world of today, and its international shows, remains unthinkable without drawing. But what is it that makes the drawing of the last two decades so special and so attractive for both the producer as well as for the beholder?

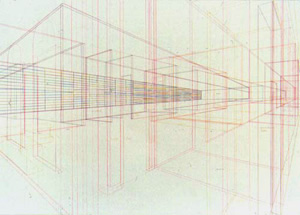

Such recent interest in drawing, however, is accompanied also by a different approach to drawing itself: an exposed reflexive outlook and a denial of concepts of modernism. In comparison to former concepts of drawing, then, this means an essential shift within the practice of drawing and the artist's self-image. Traditional theories of drawing do not seem to grasp the broader contemporary notion of drawing. In other words, the former understand of drawing solely as the material upholder of an artistic idea, thus a concentrate of thought, or primarily as a self-referential expression. Such an immediate expression of subjectivity, however, struggles with a sort of drawing that delineates a space beyond these implications. Contemporary drawing contains, for example, scientific-like acts of recording, which translate and transform scientific series of experiments and research into the logic of artistic drawing (as in the work of Mark Dion or Mark Lombardi), as well as a constructive-reconstructive process as the operative method of appropriation of reality (as in the work of Silke Schatz). Also linked to this ethos is the rebounding of drawing to an intensive physicality, a maniacal generation of traces that play a role for example in the series of Hotel-drawings by Martin Kippenberger.

The rise of drawing is not only grounded in its specific paper surface, which might be noted as an offer of resistance against the slickness of new media, the work on paper also holds a specific epistemological status that resides in its materiality. Drawing as a means of knowledge is based on a whole set of conditions and precautions, which include not only the mind and the consciousness, respectively, and the product of a marked paper, but is also a matter of the focus on the complex process of drawing, the execution and act of which is visible as a surplus of the representation on the surface of the image supporter. Drawing is, therefore, a delicate structure between tools (pen), material (paper), body (hand, perception) and consciousness. It is at this structural moment of the drawing act that is of particular interest, especially as a describable action: as an act of recording, as the ability to make a choice that inscribes to the »inaugural blankness« (Norman Bryson) a work-process.

Which kinds of recording systems have been generated for which sorts of knowledge? Assuming that certain kinds of capacity are used for specific problems of representation, we can also assume that there exists a particular regulation within the procedure that accompanies drawing as a premise of decision. Is there, furthermore, a logic of procedure in contemporary drawing?

[PHOTOGRAPHY/COPYRIGHT CREDITS]

Silke Schatz: Concert hall (ground floor), 1999. Pencil and crayon on paper